Coronavirus December 2020—Part 11 Should You Get the Moderna Vaccine?

In this post, we answer your questions about the Moderna vaccine, which was just authorized by the FDA for distribution. As usual, if you’re less interested in how we got to our conclusions than you are in the conclusions themselves, feel free to skip to the BOTTOM LINE in each section and the CONCLUSION at the end. (This post is very similar to our last post on the Pfizer vaccine, with a few important differences, noted in the text.)

Question: Should you get the vaccine when it becomes available to you?

Answer: Yes.

Nuts and bolts of the MODERNA vaccine

Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine has been dubbed MRNA-1273. Like Pfizer’s vaccine, it’s an RNA vaccine. This means that unlike other vaccines, which use weakened or killed viruses, the Moderna vaccine uses only a piece of viral RNA. The piece of viral RNA used in MRNA-1273 codes for a piece of the spike protein, the part of the SARS-CoV-2 virus that enables it to attach to and enter human cells. The body then manufactures neutralizing antibodies to that part of the virus, meaning antibodies that have the ability to prevent active infection.

The vaccine regimen includes two doses spaced 28 days apart. After thawing, MRNA-1273 will remain stable at standard refrigerator temperatures of 2° to 8°C (36° to 46°F) for up to 30 days within the 6-month shelf life. It’s given intramuscularly (in the shoulder muscle). The vaccine is preservative free.

Importantly, the analysis of the Moderna trial has thus far only included subjects 18 years of age and older.

BOTTOM LINE: The Moderna study, like the Pfizer study, included subjects representative of the general population and utilized a new strategy (RNA) to induce immunity. The one deficiency is that, so far, Moderna has only tested the vaccine in people 18 years of age and older and its use can only be generalized at this point to that group.

How are Vaccines Proven to be safe?

As we discussed in previous posts about COVID-19, vaccines are studied in three phases, each subsequent phase recruiting more subjects than the previous phases to test vaccine efficacy and safety. These studies are randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled—the gold-standard study design—because only randomized, controlled trials can definitively prove an intervention works and that it’s safe.

It turns out that, historically, most adverse reactions to vaccines occur within the first two months of vaccination. This is why Moderna applied for Emergency Use Authorization once most of the subjects in its study had been observed for 2 months after receiving the second dose of vaccine (the study is planned to go out 2 years before concluding). Post-marketing studies—long-term surveillance efforts looking for adverse events after a vaccine has been given to millions of people—have identified adverse events not seen in initial vaccine studies, but these events are, almost by definition, rare given the large numbers of subjects tested in Phase III trials (for example, Guillain-Barre syndrome occurring after a flu shot at a rate of literally 1 in a million). While questions have been raised about some vaccines causing, among other things, sudden infant death syndrome, pediatric asthma, autism, inflammatory bowel disease, and permanent brain damage, in each case, studies have revealed these claims to be groundless.

As with Pfizer’s vaccine, a reasonable concern about MRNA-1273 is that few RNA vaccines have been studied in humans. Could there be long-term risks associated with this vaccine strategy? The answer is, of course, yes. However, it’s unlikely. The RNA vaccine strategy has been studied for more than a decade. RNA vaccines don’t contain live virus so cannot cause disease. Also, the RNA doesn’t enter the nucleus of human cells and doesn’t interact with a subject’s DNA at all. After causing cells to produce the protein against which the immune system will develop antibodies, the RNA is degraded by normal cellular mechanisms. Many studies of RNA vaccines against cancer have been done—though these have all been Phase I or II trials, which means tens or hundreds of subjects tested instead of thousands—but the length of surveillance for adverse reactions has been longer—from 15 weeks to 5 years, and none have shown any long-term serious side effects.

What have been the adverse events in the Moderna study? The most common were injection site pain (88.2 percent), fatigue (65.3 percent), headache (58.6 percent), muscle pain (58 percent), chills (44.2 percent), joint pain (42.8 percent), fever (15.5 percent). Interestingly, these complication rates are nearly identical to the rates for the Pfizer vaccine, with the exception of muscle pain and joint pain, which were both about 15 – 20 percent higher for the Moderna vaccine. The frequency of serious adverse events was less than 0.1 percent (less than 0.5 percent for the Pfizer vaccine) and, importantly, evenly divided between the vaccine group and the placebo group. There were no cases of Bell’s palsy in the vaccine group (compared to four in the Pfizer study, all in the vaccine group), though it’s important to note that four cases in the vaccine group in the Pfizer study don’t represent a frequency above that expected in the general population. Severe adverse reactions were also less common in subjects older than 65. Reactions were more frequent and more severe after the second injection in all age groups.

There were a total of thirteen deaths in the study, six in the vaccine group and seven in the placebo group. Deaths were caused in the vaccine group by heart attacks, suicide, head injury, and multi-system organ failure and in the placebo group by heart attacks, abdominal injury, and, in one case, COVID-19. These aren’t rates higher than expected in the general population and therefore aren’t attributed to the vaccine.

Bottom line: Like the Pfizer vaccine, the Moderna vaccine is safe. Any adverse events not yet identified will almost certainly be rare. No other RNA vaccine tested in humans has produced any serious long-term adverse events. By the time members of the general public are able to get the Moderna vaccine, we’ll have even more months of observation.

How are Vaccines Proven to be Effective?

The Moderna Phase III study randomized 30,418 subjects to receive either the vaccine or placebo. They chose to include 30,418 subjects because they needed a sample size large enough to yield a sufficient number of cases of COVID-19 to tell if there was a statistically significant difference in infection rates between subjects who got the vaccine and subjects who got the placebo, and to detect rarer adverse events from the vaccine. By the time Moderna submitted their application to the FDA for Emergency Use Authorization, there had been 196 cases of COVID-19 in their study participants, a number similar to that in trials testing vaccines for other diseases.

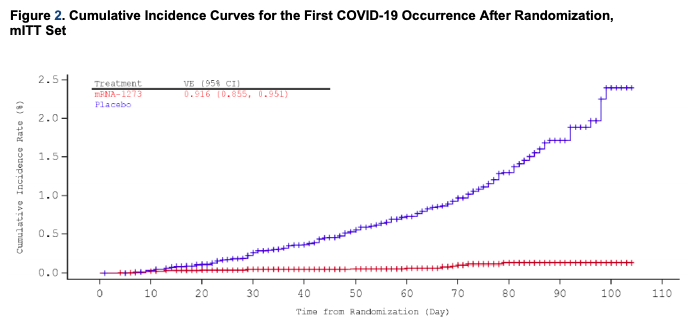

Moderna found that their vaccine overall has a 94.1 percent efficacy rate (essentially identical to Pfizer’s 95 percent efficacy rate). Vaccine efficacy is defined as the reduction in risk that vaccination provides in a clinical trial (when conditions are as perfect as they’re ever going to be). So a 94.1 percent vaccine efficacy means vaccination reduces the baseline risk (which differs in different circumstances) of getting COVID-19 by 94.1 percent. So, for example, if your baseline risk of getting COVID-19 from, say, your infected spouse is 27.8 percent (the highest risk reported in a clinical trial that we’ve seen), the risk of getting COVID-19 from your infected spouse if you’ve been vaccinated would be 94.1 percent less, or 1.6 percent.

This is an outstanding level of risk reduction for a vaccine. For comparison, flu shots have an efficacy of 40 to 60 percent. The polio vaccine has an efficacy of 99 to 100 percent. The hepatitis B vaccine has an efficacy of 80 to 100 percent.

No subjects with proven prior COVID-19 infection were included in the study, so we don’t know if vaccination reduces the likelihood of re-infection. Pregnant women were excluded from the trial, as were women who were breastfeeding and subjects who were immunocompromised, so we can’t say what effect or risk the vaccine brings to those groups.

The graph below illustrates the cumulative incidence of COVID-19 infection between subjects in the vaccination group and subjects in the placebo group, which begins to diverge 14 days after the time of the first vaccine injection:

Importantly, as with the Pfizer vaccine, Moderna’s vaccine seems to be effective across age groups (above age 18), genders, racial and ethnic groups, and subjects with medical conditions associated with high risk for severe COVID-19.

Unlike the Pfizer study in which only 4 subjects developed severe COVID-19 (1 in the vaccine group and 3 in the placebo group), in the Moderna study 30 subjects developed severe COVID-19 and all were in the placebo group. This argues for a 100 percent efficacy in preventing severe COVID-19.

Bottom line: Moderna’s vaccine is highly effective for most people over the age of 18. It also appears that it prevents severe COVID-19.

Unanswered Questions

- The study didn’t look to see if the vaccine prevents asymptomatic infection. Nor did it assess whether subjects who developed COVID-19 despite vaccination are less likely to transmit the virus. Thus, it’s not yet clear how effective the vaccine will be in containing the spread of the infection.

- The study hasn’t gone on long enough to tell if subjects who were vaccinated yet still contracted COVID-19 have a lower risk of long-term effects of COVID-19.

- We don’t yet know if the vaccine reduces the risk of dying from COVID-19.

- There was insufficient data to draw conclusions about safety and efficacy of the vaccine in children younger than 18, pregnant or breastfeeding women, and patients who are immunocompromised.

- We don’t yet know how long immunity lasts and whether or not booster shots will be necessary.

Practical Considerations

Though the storage requirements of the Moderna vaccine are far less stringent than those of the Pfizer vaccine, it’s unclear how and from where the majority of Americans will receive their doses. We’re waiting to hear from the government how the vaccine will be distributed and who will be eligible to receive it and when. (We haven’t received our own vaccinations at ImagineMD yet.)

As soon as more information is made available to us about distribution, we’ll make that information available to you. Almost certainly, the general public will not be able to get vaccinated until sometime next year, in 2021.

Conclusions

- The vaccine is highly effective in preventing symptomatic COVID-19 infection.

- The vaccine is safe. Adverse reactions, both local and systemic, are mostly minor. Though the study hasn’t yet gone on long enough to prove there are no serious long-term adverse affects, such adverse affects, if they exist, are likely to be rare and non-life-threatening based on other Phase I and II studies of other RNA vaccines.

- We recommend everyone who is eligible to receive the vaccine should receive it when it becomes available to them.

- It very well may take all of 2021 to get everyone who’s willing to be vaccinated to receive the shots, which means it likely won’t be until early 2022 that life returns to pre-pandemic normal. In the meantime, continue to wear a mask when indoors with anyone you don’t live with, wash your hands frequently, and refrain from dining indoors at restaurants.

- Coronavirus February 2020—Part 1 What We Know So Far

- Coronavirus March 2020—Part 2 Measures to Protect Yourself

- Supporting Employee Health During the Coronavirus Pandemic

- Coronavirus March 2020—Part 3 Symptoms and Risks

- Coronavirus March 2020—Part 4 The Truth about Hydroxychloroquine

- Coronavirus April 2020—Part 5 The Real Risk of Death

- Coronavirus April 2020—Part 6 Evaluating Diagnostic Tests

- Coronavirus April 2020—Part 7 The Accuracy of Our Antibody Test

- Coronavirus May 2020—Part 8 How to Reopen a Business Safely

- Coronavirus August 2020—Part 9 Masks, Vaccines, and Rapid Testing

- Coronavirus December 2020—Part 10 Should You Get the Pfizer Vaccine?

[jetpack_subscription_form title=” subscribe_text=’Sign up to get notified when a new blog post has been published.’ subscribe_button=’Sign Me Up’ show_subscribers_total=’0′]

This post shows a different type of cumulative incidence curve plot from the one shown in the Pfizer vaccine post. The plot for this vaccine that is like the one for Pfizer is on page 26 of https://www.fda.gov/media/144434/download. The plot in this post makes it look like there is no advantage in being vaccinated until day 42 after the first shot, whereas the plots of the less filtered data show divergence of the two curves at about 8-10 days after the first shot.