A Prescription For The Healthcare Crisis

With all the shouting going on about America’s healthcare crisis, many are probably finding it difficult to concentrate, much less understand the cause of the problems confronting us. I find myself dismayed at the tone of the discussion (though I understand it—people are scared) as well as bemused that anyone would presume themselves sufficiently qualified to know how to best improve our healthcare system simply because they’ve encountered it, when people who’ve spent entire careers studying it (and I don’t mean politicians) aren’t sure what to do themselves.

Albert Einstein is reputed to have said that if he had an hour to save the world he’d spend 55 minutes defining the problem and only 5 minutes solving it. Our healthcare system is far more complex than most who are offering solutions admit or recognize, and unless we focus most of our efforts on defining its problems and thoroughly understanding their causes, any changes we make are just likely to make them worse as they are better.

Though I’ve worked in the American health care system as a physician since 1992, have seven year’s worth of experience as an administrative director of primary care, and have worked in direct primary care, I don’t consider myself qualified to thoroughly evaluate the viability of most of the suggestions I’ve heard for improving our healthcare system. I do think, however, I can at least contribute to the discussion by describing some of its troubles, taking reasonable guesses at their causes, and outlining some general principles that should be applied in attempting to solve them.

THE PROBLEM OF COST

No one disputes that health care spending in the U.S. has been rising dramatically. According to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), healthcare spending is projected to reach $8,160 per person per year by the end of 2009 compared to the $356 per person per year it was in 1970. This increase occurred roughly 2.4% faster than the increase in GDP over the same period. Though GDP varies from year-to-year and is therefore an imperfect way to assess a rise in health care costs in comparison to other expenditures from one year to the next, we can still conclude from this data that over the last 40 years the percentage of our national income (personal, business, and governmental) we’ve spent on health care has been rising.

Despite what most assume, this may or may not be bad. It all depends on two things: the reasons why spending on health care has been increasing relative to our GDP and how much value we’ve been getting for each dollar we spend.

WHY HAS HEALTHCARE BECOME SO COSTLY?

This is a harder question to answer than many would believe. The rise in the cost of health care (on average 8.1% per year from 1970 to 2009, calculated from the data above) has exceeded the rise in inflation (4.4% on average over that same period), so we can’t attribute the increased cost to inflation alone. Health care expenditures are known to be closely associated with a country’s GDP (the wealthier the nation, the more it spends on health care), yet even in this the United States remains an outlier.

Is it because of spending on health care for people over the age of 75 (five times what we spend on people between the ages of 25 and 34) No. Studies show this demographic trend explains only a small percentage of health expenditure growth.

Is it because of monstrous profits the health insurance companies are raking in? Probably not. It’s admittedly difficult to know for certain as not all insurance companies are publicly traded and therefore have balance sheets available for public review. But Aetna, one of the largest publicly traded health insurance companies in North America, reported a 2009 second quarter profit of $346.7 million, which, if projected out, predicts a yearly profit of around $1.3 billion from the approximately 19 million people they insure. If we assume their profit margin is average for their industry (even if untrue, it’s unlikely to be orders of magnitude different from the average), the total profit for all private health insurance companies in America, which insured 202 million people in 2007, would come to approximately $13 billion per year. Total health care expenditures in 2007 were $2.2 trillion, which yields a private health care industry profit approximately 0.6% of total health care costs (though this analysis mixes data from different years, it can perhaps be permitted as the numbers aren’t likely different by any order of magnitude).

Is it because of health care fraud? Estimates of losses due to fraud range as high as 10% of all health care expenditures, but it’s hard to find hard data to back this up. Though some percentage of fraud almost certainly goes undetected, perhaps the best way to estimate how much money is lost due to fraud is by looking at how much the government actually recovers. In 2006, this was $2.2 billion, only 0.1% of $2.1 trillion in total health care expenditures for that year.

Is it due to pharmaceutical costs? In 2006, total expenditures on prescription drugs was approximately $216 billion. Though this amounted to 10% of the $2.1 trillion in total health care expenditures for that year and must therefore be considered significant, it still remains only a small percentage of total health care costs.

Is it from administrative costs? In 1999, total administrative costs were estimated to be $294 billion, a full 25% of the $1.2 trillion in total health care expenditures that year. This was a significant percentage in 1999 and it’s hard to imagine it’s shrunk to any significant degree since then.

In the end, though, what probably has contributed the greatest amount to the increase in health care spending in the U.S. are two things:

-

- Technological innovation.

- Over-utilization of healthcare resources by both patients and healthcare providers themselves.

Technological innovation. Data that proves increasing healthcare costs are due mostly to technological innovation is surprisingly difficult to obtain, but estimates of the contribution to the rise in healthcare costs due to technological innovation range anywhere from 40% to 65%. Though we mostly only have empirical data for this, several examples illustrate the principle. Heart attacks used to be treated with aspirin and prayer. Now they’re treated with drugs to control shock, pulmonary edema, and arrhythmias as well as thrombolytic therapy, cardiac catheterization with angioplasty or stenting, and coronary artery bypass grafting. You don’t have to be an economist to figure out which scenario ends up being more expensive. We may learn to perform these same procedures more cheaply over time (the same way we’ve figured out how to make computers cheaper) but as the cost per procedure decreases, the total amount spent on each procedure goes up because the number of procedures performed goes up. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is 25% less than the price of an open cholecystectomy, but the rates of both have increased by 60%. As technological advances become more widely available, they become more widely used, and one thing we’re great at doing in the United States is making technology available.

Over-utilization of healthcare resources by both patients and health care providers themselves. We can easily define over-utilization as the unnecessary consumption of healthcare resources. What’s not so easy is recognizing it. Every year from October through February the majority of patients who come into the Urgent Care Clinic at my hospital are, in my view, doing so unnecessarily. What are they coming in for? Colds. I can offer support, reassurance that nothing is seriously wrong, and advice about over-the-counter remedies—but none of these things will make them better faster (though I often am able to reduce their level of concern). Further, patients have a hard time believing the key to arriving at a correct diagnosis lies in history gathering and careful physical examination rather than technologically-based testing (not that the latter isn’t important—just less so than most patients believe). Just how much patient-driven over-utilization costs the healthcare system is hard to pin down as we have mostly only anecdotal evidence as above. There is emerging evidence, however, that direct primary care reduces this over-utilization and therefore reduces the cost of healthcare.

Further, doctors often disagree among themselves about what constitutes unnecessary healthcare consumption. In his excellent article, “The Cost Conundrum,” Atul Gawande argues that regional variation in over-utilization of healthcare resources by doctors best accounts for the regional variation in Medicare spending per person. He goes on to argue that if doctors could be motivated to rein in their over-utilization in high-cost areas of the country, it would save Medicare enough money to keep it solvent for 50 years.

A reasonable approach. To get that to happen, however, we need to understand why doctors are over-utilizing healthcare resources in the first place:

-

- Judgment varies in cases where the medical literature is vague or unhelpful. When faced with diagnostic dilemmas or diseases for which standard treatments haven’t been established, a variation in practice invariably occurs. If a primary care doctor suspects her patient has an ulcer, does she treat herself empirically or refer to a gastroenterologist for an endoscopy? If certain “red flag” symptoms are present, most doctors would refer. If not, some would and some wouldn’t depending on their training and the intangible exercise of judgment.

- Inexperience or poor judgment. More experienced physicians tend to rely on histories and physicals more than less experienced physicians and consequently order fewer and less expensive tests. Studies suggest primary care physicians spend less money on tests and procedures than their sub-specialty colleagues but obtain similar and sometimes even better outcomes.

- Fear of being sued. This is especially common in emergency room settings, but extends to almost every area of medicine.

- Patients tend to demand more testing rather than less. As noted above. And physicians often have difficulty refusing patient requests for many reasons (e.g., wanting to please them, fear of missing a diagnosis and being sued, etc.).

- In many settings, over-utilization makes doctors more money. here exists no reliable incentive for doctors to limit their spending unless their pay is capitated or they’re receiving a straight salary.

Gawande’s article implies there exists some level of utilization of healthcare resources that’s optimal: use too little and you get mistakes and missed diagnoses; use too much and excess money gets spent without improving outcomes, paradoxically sometimes resulting in outcomes that are actually worse (likely as a result of complications from all the extra testing and treatments).

How then can we get doctors to employ uniformly good judgment to order the right number of tests and treatments for each patient—the “sweet spot”—in order to yield the best outcomes with the lowest risk of complications? Not easily. There is, fortunately or unfortunately, an art to good health care resource utilization. Some doctors are more gifted at it than others. Some are more diligent about keeping current. Some care more about their patients. An explosion of studies of medical tests and treatments has occurred in the last several decades to help guide doctors in choosing the most effective, safest, and even cheapest ways to practice medicine, but the diffusion of this evidence-based medicine is a tricky business. Just because beta blockers, for example, have been shown to improve survival after heart attacks doesn’t mean every physician knows it or provides them. Data clearly show many don’t. How information spreads from the medical literature into medical practice is a subject worthy of an entire post unto itself. Getting it to happen uniformly has proven extremely difficult.

In summary, then, most of the increase in spending on healthcare seems to have come from technological innovation coupled with its overuse by doctors working in systems that motivate them to practice more medicine rather than better medicine, as well as patients who demand the former thinking it yields the latter.

But even if we could snap our fingers and magically eliminate all over-utilization today, health care in the U.S. would still remain among the most expensive in the world, requiring us to ask next—

WHAT VALUE ARE WE GETTING FOR THE DOLLARS WE SPEND?

According to an article in the New England Journal of Medicine titled “The Burden of Health Care Costs for Working Families—Implications for Reform,” growth in health care spending “can be defined as affordable as long as the rising percentage of income devoted to healthcare does not reduce standards of living. When absolute increases in income cannot keep up with absolute increases in healthcare spending, healthcare growth can be paid for only by sacrificing consumption of goods and services not related to health care.” When would this ever be an acceptable state of affairs? Only when the incremental cost of health care buys equal or greater incremental value. If, for example, you were told that in the near future you’d be spending 60% of your income on health care but that as a result you’d enjoy, say, a 30% chance of living to the age of 250, perhaps you’d judge that 60% a small price to pay.

This is what the debate on health care spending really needs to be about. Certainly we should work on ways to eliminate over-utilization. But the real question isn’t what absolute amount of money is too much to spend on health care. The real question is what are we getting for the money we spend and is it worth what we have to give up?

People who are alarmed by the notion that as health care costs increase, policymakers may decide to ration health care don’t realize that we’re already rationing at least some of it. It just doesn’t appear as if we are because we’re rationing it on a first-come-first-serve basis—leaving it at least partially up to chance rather than to policy, which we’re uncomfortable defining and enforcing. Thus we don’t realize the reason our 90-year-old father in Illinois can’t have the liver he needs is because a 14-year-old girl in Alaska got in line first (or maybe our father was in line first and gets it while the 14 year-old girl doesn’t). Given that most of us remain uncomfortable with the notion of rationing health care based on criteria like age or utility to society, as technological innovation continues to drive up healthcare spending, we very well may at some point have to make critical judgments about which medical innovations are worth our entire society sacrificing access to other goods and services (unless we’re so foolish as to repeat the critical mistake of believing we can keep borrowing money forever without ever having to pay it back).

So what value are we getting? It varies. The risk of dying from a heart attack has declined by 66% since 1950 as a result of technological innovation. Because cardiovascular disease ranks as the number one cause of death in the U.S., this would seem to rank high on the scale of value as it benefits a huge proportion of the population in an important way. As a result of advances in pharmacology, we can now treat depression, anxiety, and even psychosis far better than anyone could have imagined even as recently as the mid-1980’s (when Prozac was first released). Clearly, then, some increases in health care costs have yielded enormous value we wouldn’t want to give up.

But how do we decide whether we’re getting good value from new innovations? Scientific studies must prove the innovation (whether a new test or treatment) actually provides clinically significant benefit (Aricept is a good example of a drug that works but doesn’t provide great clinical benefit—demented patients score higher on tests of cognitive ability while on it but probably aren’t significantly more functional or significantly better able to remember their children compared to when they’re not). But comparative effectiveness studies are extremely costly, take a long time to complete, and can never be perfectly applied to every individual patient, all of which means some healthcare provider always has to apply good medical judgment to every patient problem.

Who’s best positioned to judge the value to society of the benefit of an innovation—that is, to decide if an innovation’s benefit justifies its cost? I would argue the group that ultimately pays for it: the American public. How the public’s views could be reconciled and then effectively communicated to policy makers efficiently enough to affect actual policy, however, lies far beyond the scope of this post (and perhaps anyone’s imagination).

THE PROBLEM OF ACCESS

A significant proportion of the population is uninsured or underinsured, limiting or eliminating their access to healthcare. As a result, this group finds the path of least (and cheapest) resistance—emergency rooms—which has significantly impaired the ability of our nation’s ER physicians to actually render timely emergency care. In addition, surveys suggest a looming primary care physician shortage relative to the demand for their services. In my view, this imbalance between supply and demand explains most of the poor customer service patients face in our system every day: long wait times for doctors’ appointments, long wait times in doctors’ offices once their appointment day arrives, then short times spent with doctors inside exam rooms, followed by difficulty reaching their doctors in between office visits, and finally delays in getting test results. This imbalance would likely only partially be alleviated by less healthcare over-utilization by patients.

GUIDELINES FOR SOLUTIONS

As Freaknomics authors Steven Levitt and Stephen Dubner state, “If morality represents how people would like the world to work, then economics represents how it actually does work.” Capitalism is based on the principle of enlightened self-interest, a system that creates incentives to yield behavior that benefits both suppliers and consumers and thus society as a whole. But when incentives get out of whack, people begin to behave in ways that continue to benefit them often at the expense of others or even at their own expense down the road. Whatever changes we make to our healthcare system (and there’s always more than one way to skin a cat), we must be sure to align incentives so that the behavior that results in each part of the system contributes to its sustainability rather than its ruin.

Here then is a summary of what I consider the best recommendations I’ve come across to address the problems I’ve outlined above:

-

- Change the way insurance companies think about doing business. Insurance companies have the same goal as all other businesses: maximize profits. And if a health insurance company is publicly traded and in your 401k portfolio, you want them to maximize profits, too. Unfortunately, the best way for them to do this is to deny their services to the very customers who pay for them. It’s harder for them to spread risk (the function of any insurance company) relative to say, a car insurance company, because far more people make health insurance claims than car insurance claims. It would seem, therefore, from a consumer perspective, the private health insurance model is fundamentally flawed. We need to create a disincentive for health insurance companies to deny claims (or, conversely, an extra incentive for them to pay them). Allowing and encouraging across-state insurance competition might at least partially engage free market forces to drive down insurance premiums as well as open up new markets to local insurance companies, benefiting both insurance consumers and providers. With their customers now armed with the all-important power to go elsewhere, health insurance companies might come to view the quality with which they actually provide service to their customers (i.e., the paying out of claims) as a way to retain and grow their business. For this to work, monopolies or near-monopolies must be disbanded or at the very least discouraged. Even if it does work, however, government will probably still have to tighten regulation of the health insurance industry to ensure some of the heinous abuses that are going on now stop (for example, insurance companies shouldn’t be allowed to stratify consumers into subgroups based on age and increase premiums based on an older group’s higher average risk of illness because healthy older consumers then end up being penalized for their age rather than their behaviors). Karl Denninger suggests some intriguing ideas in a post on his blog about requiring insurance companies to offer identical rates to businesses and individuals as well as creating a mandatory “open enrollment” period in which participants could only opt in or out of a plan on a yearly basis. This would prevent individuals from only buying insurance when they got sick, eliminating the adverse selection problem that’s driven insurance companies to deny payment for pre-existing conditions. I would add that, however reimbursement rates to health care providers are determined in the future (again, an entire post unto itself), all health insurance plans, whether private or public, must reimburse health care providers by an equal percentage to eliminate the existence of “good” and “bad” insurance that’s currently responsible for motivating hospitals and doctors to limit or even deny service to the poor, and which may be responsible for the same thing occurring to the elderly in the future (Medicare reimburses only slightly better than Medicaid). Finally, regarding the idea of a “public option” insurance plan open to all, I worry that if it’s significantly cheaper than private options while providing near-equal benefits the entire country will rush to it en masse, driving private insurance companies out of business and forcing us all to subsidize one another’s health care with higher taxes and fewer choices; yet at the same time if the cost to the consumer of a “public option” remains comparable to private options, the very people it’s meant to help won’t be able to afford it.

- Motivate the population to engage in healthier lifestyles that have been proven to prevent disease. Prevention of disease probably saves money, though some have argued that living longer increases the likelihood of developing diseases that wouldn’t have otherwise occurred, leading to the overall consumption of more healthcare dollars (though even if that’s true, those extra years of life would be judged by most valuable enough to justify the extra cost. After all, the whole purpose of health care is to improve the quality and quantity of life, not save society money. Let’s not put the cart before the horse). However, the idea of preventing a potentially bad outcome sometime in the future is only weakly motivating psychologically, explaining why so many people have so much trouble getting themselves to exercise, eat right, lose weight, stop smoking, etc. The idea of financially rewarding desirable behavior and/or financially punishing undesirable behavior is highly controversial. Though I worry this kind of strategy risks the enacting of policies that may impinge on basic freedoms if taken too far, I’m not against thinking creatively about how we could leverage stronger motivational forces to help people achieve health goals they themselves want to achieve. After all, most obese people want to lose weight. Most smokers want to quit. They might be more successful if they could find more powerful motivation.

- Decrease over-utilization of health care resources by doctors. I’m in agreement with Gawande that finding ways to get doctors to stop over-utilizing healthcare resources is a worthy goal that will significantly rein in costs, that it will require a willingness to experiment, and that it will take time. Further, I agree that focusing only on who pays for our health care (whether the public or private sectors) will fail to address the issue adequately. But how exactly can we motivate doctors, whose pens are responsible for most of the money spent on healthcare in this country, to focus on what’s truly best for their patients? The idea that external bodies—whether insurance companies or government panels—could be used to set standards of care doctors must follow in order to control costs strikes me as ludicrous. Such bodies have neither the training nor overriding concern for patients’ welfare to be trusted to make those judgments. Why else do we have doctors if not to employ their expertise to apply nuanced approaches to complex situations? As long as they work in a system free of incentives that compete with their duty to their patients, they remain in the best position to make decisions about what tests and treatments are worth a given patient’s consideration—as long as they’re careful to avoid overconfident paternalism (refusing to obtain a head CT for a headache might be paternalistic; refusing to offer chemotherapy for a cold isn’t). So perhaps we should eliminate any financial incentive doctors have to care about anything but their patients’ welfare, meaning doctors’ salaries should be disconnected from the number of surgeries they perform and the number of tests they order, and should instead be set by market forces. This model already exists in academic health care centers and hasn’t seemed to promote shoddy care when doctors feel they’re being paid fairly. Doctors need to earn a good living to compensate for the years of training and massive amounts of debt they amass, but no financial incentive for practicing more medicine should be allowed to attach itself to that good living.

- Decrease over-utilization of health care resources by patients. This, it seems to me, requires at least three interventions:

-

-

-

- Making available the right resources for the right problems (so that patients aren’t going to the ER for colds, for example, but rather to their primary care physicians). This would require hitting the “sweet spot” with respect to the number of primary care physicians, best at front-line gatekeeping, not of health care spending as in the old HMO model, but of triage and treatment. It would also require a recalculating of reimbursement levels for primary care services relative to specialty services to encourage more medical students to go into primary care (the reverse of the alarming trend we’ve been seeing for the last decade).

- A massive effort to increase the health literacy of the general public to improve its ability to triage its own complaints (so patients don’t actually go anywhere for colds or demand MRIs of their backs when their trusted physicians tells them it’s just a strain). This might be best accomplished through a series of educational programs (though given that no one in the private sector has an incentive to fund such programs, it might actually be one of the few things the government should—we’d just need to study and compare different educational programs and methods to see which, if any, reduce unnecessary patient utilization without worsening outcomes and result in more health care savings than they cost).

- Redesigning insurance plans to make patients in some way more financially liable for their health care choices. We can’t have people going bankrupt due to illness, nor do we want people to underutilize health care resources (avoiding the ER when they have chest pain, for example), but neither can we continue to support a system in which patients are actually motivated to over-utilize resources, as the current “pre-pay for everything” model does.

-

-

CONCLUSION

Given the enormous complexity of the healthcare system, no single post could possibly address every problem that needs to be fixed. Significant issues not raised in this article include the challenges associated with rising drug costs, direct-to-consumer marketing of drugs, end-of-life care, sky-rocketing malpractice insurance costs, the lack of cost transparency that enables hospitals to paradoxically charge the uninsured more than the insured for the same care, extending health care insurance coverage to those who still don’t have it, improving administrative efficiency to reduce costs, the implementation of electronic medical records to reduce medical error, the financial burden of businesses being required to provide their employees with health insurance, and tort reform. All are profoundly interdependent, standing together like the proverbial house of cards. To attend to any one is to affect them all, which is why rushing through health care reform without careful contemplation risks unintended and potentially devastating consequences. Change does need to come, but if we don’t allow ourselves time to think through the problems clearly and cleverly and to implement solutions in a measured fashion, we risk bringing down that house of cards rather than cementing it.

[jetpack_subscription_form title=” subscribe_text=’Sign up to get notified when a new blog post has been published.’ subscribe_button=’Sign Me Up’ show_subscribers_total=’0′]

While I agree that no one person could possibly hold all the answers in this byzantine health care environment we’ve created in the United States, I can attest to the fact that much of the complexity causes the problem, and has no useful purpose. Let me give you a few examples.

1. “Pool” based underwriting. Insurers divide policy holders into “pools” to create prices for these arbitrarily defined groups. This creates more work for underwriters, so a negative spiral of hiring more people to deny care who are supported by the money earned through denying that care ensues. Elimination of all “pool” based underwriting decreases the size of insurers and lowers cost dramatically.

2. Two-tier insurance. Rather than the thousands of insurance “products” with limitless bells and whistles, exclusions and attributes, one basic quality policy, similar to Medicare, should be mandated as available from every insurance company. For extra features, insurers should be allowed to offer add-on “gap” policies to cover extras. Sounds like Medicare, huh? So you know it works!

3. Pharmaceutical marketing. All traditional media marketing directed at consumers increases pharmaceutical costs while weakening the doctor-patient bond. Web publishing of drugs and their attributes should be sufficient public notice. Elimination of TV, radio, print and all other pharmaceutical consumer marketing only makes sense; there is no other country in the world weak-willed enough to permit this waste of money and misdirected effort.

4. Primary care “fee-for-service” billing. Doctors are paid for providing services and procedures, not for helping patients achieve better outcomes. Guidelines for a complete paradigm shift on primary care certainly exist and can be implemented, along with free four-year education for those able to stand the rigors of med school and willing to commit to primary care for at least 10 years after graduation. Physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and chiropractors should be included here as well.

5. Electronic billing and records. I personally could create, test and implement a national claims form and integrate it into every medical office and lab in this country in six months. I did the very first electronic claim payment in the US 15 years ago, and could get this done with very little fanfare or problem. We need it; this is one area where the cost savings are obvious and a freeware project to get it done should be immediately mandated so that insurers would be required to accept the claims so created. We’ve got to get our doctors off the phone with the insurer so he/she has time to see patients.

See? Health care or health insurance reform isn’t really that difficult when you take away the unnecessary complexity that’s been added to create the shell game that we currently call health insurance in the United States. It isn’t that insurance companies have profits that are too high so much as it is that they have too many people working at making health care decisions and have come to take in too many health care dollars. Pharmaceuticals have built growth markets creating designer drugs for sophisticated marketing campaigns, again sopping up billions of health care dollars that could be used to provide medical or preventive care services for the currently under—or uninsured.

And no, it can’t all be covered in one article (or even one comment) but it certainly isn’t rocket science. Yet. Add a little more complexity, and I’m sure it’ll get there.

I forgot to mention how much I enjoy this blog. Reading it is the high point of my Sunday and gets me set to take whatever comes my way throughout the week.

Thank you so much!

Alex, this is an excellent, thoughtful, apolitical discussion that ought to be required reading for all of our U.S. Senators and Representatives. Perhaps a few of them would get the message that the subject of health care is far more complicated and interdependent that they realize. Therefore, they need to tread very, very carefully—because any well-meaning “reforms” they enact are far more likely to result in adverse unintended consequences than in real improvements.

Indeed, Congress’ past track record is replete with examples of laws passed with the best of intentions, but that nevertheless ended up causing far more, and in many cases, far more serious, problems than they solved. As just one recent example, consider the case of the Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act (CPSIA). One year ago, it was enacted with the universally approved aim of stopping the importation of dangerous lead-laced toys from China. Only later did we learn that among its myriad other unintended side effects, the law also bans the distribution of children’s books printed before 1985.

CPSIA was intentionally written in such a manner as to give the Consumer Product Safety Commission no discretion in determining whether or not the law applies to a given situation. At the same time, its specific requirements are so nebulous that in reality, the specific requirements of the law are, basically, whatever the Commission says they are. The perverse end result is to make it impractical or impossible for thousands of small, specialized companies with limited resources to remain in the business of furnishing low-volume items intended for children, while rewarding the very same huge, big-box store chains that caused the problem in the first place by importing cheap junk from China—since they are the only ones with sufficiently deep pockets to comply with the new law.

Oddly enough, the exact same House committee chairman, Rep. Henry Waxman (D-CA), who is primarily responsible for the disastrous, gotcha-filled CPSIA is also the prime mover behind the House health care reform bill, as well as the even more disastrous cap-and-trade measure already approved by the House, but thankfully not yet passed by the Senate.

In view of their abysmal record, why should we have any confidence that Rep. Waxman and his myrmidons will do a better job with the infinitely more complex task of health care reform than they did with the CPSIA and the cap-and-trade bill? On the contrary, it seems to me that we would be well-advised to keep these arrogant know-it-alls as far away from our health care as possible.

Do you want me to order less testing? Then make it unprofitable for the 50 law firms that advertise all over radio, subway cars, billboards to make the monstrous money they feel they are entitled to.

Cap their pay at $50/hour for the “Pain and Suffering” portions of the lawsuits they bring and make sure they document and code what they did. The reimbursement should come from an insurance company on behalf of the patient and structured in such a way that the insurance company makes more money if they deny claims by figuring out that the lawyers did wrong.

You make some interesting points. But cost is more than “….what are we getting for the money we spend and is it worth what we have to give up?”

It’s also the absolute cost.

With my self-paid insurance and co-pays of $15K in 2008—I can’t afford increasing costs on a fixed income—no matter what I might get for the money. And once I qualify for Medicare, I’ll reach the donut hole in the first month! (I have MS).

Good post. Nice to hear an actual doctor weigh in on this health care debate.

I think you hit the nail on the head with the “technological innovation” being a prime contributor to health care costs. Buying and using MRI machines is expensive, as is running a modern hospital. This problem is exacerbated because it’s often government money being spent, which means no one cares how much it costs.

Clinical trials, as you note, are not a cost-effective means of judging the value of experimental therapies. There are however some cheaper alternatives which you might want to talk about in a later post.

Finally, as you point out, something has to be done about all the hypochondriacs. My father, who is a family practitioner, complains about them all the time. He suggests limiting health insurance coverage to more extreme cases (e.g. those requiring surgery) and having lesser consultations (“colds”) be paid out of pocket. I’m no freakonomist, but I predict that the $400/visit will knock down the number of unnecessary consultations about 95%.

If the government use this amount of insight and intelligence when considering the problem, we’ll be in good hands. :o)

Dr. Lickerman,

First off, THANK YOU. This is the best thing I’ve read on the American health care situation. Obama’s health care reform push has now degenerated into a political donnybrook over triage and killing granny. Sarah Palin may have started it, but even the NY Times has taken the bait—see today’s NYT Op Ed piece about “Health Care’s Generation Gap” (https://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/17/opinion/17dooling.html ). Doctor, you make a strong and convincing case that end-of-life and Palin’s son, Trig, are political red herrings, diverting public attention from the real problems (“cost drivers”) in health care, along with their complex social/economic/moral implications.

I am starting to believe that our nation is NOT ready at this point to implement a successful, one-shot re-design of the health care system. The President should be honest with the nation in that this is going to require many months and perhaps years of sustained focus and attention. We can’t expect to have this wrapped up by Thanksgiving. Our leaders will probably need to legislate in bits and pieces over several years, and admit that this is a BIG EXPERIMENT. Whatever legislative reforms our President signs into law may well need tweeking and modification a year or two down the road, due to the laws of unintended consequences.

Doctor, you tell us that the “meta-problem” of health care in America is very complex, but you do lay out a set of five or six major interacting features that accelerate costs. How can we expect one legislative package to successfully deal six highly complex problems? This will need to be done in stages.

At the same time, you keep us focused on the fact that increased costs are worthwhile if they give us longer and healthier lives (although at the possible cost of less consumer spending during those longer and healthier lives). Our society and our nation needs to make some VALUE judgments almost as great as those it faced during the Civil War. This is going to take time.

I would propose that the Wyden-Bennett proposal (https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=674) would be an good place to start the long-term iterative process that could eventually get our nation to a “sweet spot” with regard to health care. This “iterative process” will involve debate, legislation, follow-up analysis, new debate, new legislation…round and round. Hopefully, wisdom will grow over time and America will hone-in on greater social enlightenment for it. I would like to hear your own prescription, doctor, as to “where we go from here.” I want to hear you speak as both as a man of western scientific medicine and as a follower of the great wisdom of the east.

The Clintons tried something like this back in 1992, but let the nation down by shrugging their shoulders once the political debate heated up. I hope that Mr. Obama will not betray us in the same way, in his disappointment that many Americans are not willing to entirely trust him and his Democratic colleagues to come up with a better health care system. Health care should be kept in the limelight throughout the Obama presidency. We’ve only taken a few halting steps thus far in the journey of a thousand miles. Mr. Obama has the opportunity here to show true political courage, at the cost of tremendous political risk; he will make the choice between Chicago machine politics and Abraham Lincoln. It’s an Illinois thing, I guess.

Jim G., an “eternal student of life” (or something)

Doctor,

If I may, just a few more thoughts on your own extremely thoughtful piece. First, thank you for your gracious response to my previous comment, and for your wise thoughts in response.

Second, part of the political courage that I wish to see from our President involves putting medical tort reform back on the table, in spite of the trial lawyers lobby. I certainly want doctors to be held accountable for their mistakes, but I don’t want those mistakes dealt with using the same mechanism that society prescribes for sloppy roofing contractors and people who don’t shovel snow from their sidewalks. I’ve read of some thoughtful alternatives to the old fashioned pain-and-suffering lawsuit; alternatives that intelligently balance the public’s need to be protected from and compensated for professional negligence, against the need for professional peer judgment insulated from the emotional manipulation that trial lawyers often inject.

Third, I’ve read that one of the cost drivers in American health care is something that you can’t legislate away. For lack of a more precise term, this is “the American character,” ie., unfavorable comparisons between American health indicators and those for western European and Japanese may be influenced by the greater tolerance for risky behavior on the part of many Americans.

It is arguable that Americans generally have more auto accidents as we too frequently mix fast driving and alcohol consumption (and now we talk on the cell phone too while speeding). And then there is the effect of violent crime, especially gun use. Next, the long-term effects on the waistline from all that tasty fast food available on every main thoroughfare. And then add in smoking and other drug abuse.

Our leaders cannot legislate this away, but they can use their pulpits to help Americans who are upset about health care costs and inequities to look in the mirror. This is a time for soul-searching on the part of our nation, and Mr. Obama needs to promote and intelligently guide that process (with help from you doctors). He’s going to have to remind us that he and our other political leaders can’t fix this thing alone.

Thanks again. I honestly do hope that the doctors of our nation will unite their voices to support true and intelligent health care reform (via a long-term, slow-burn process, as we both agree).

Jim G.

Dear Dr. Lickerman,

Your voice of reason resonates with me, and I too share the concern about the “tone” and the complexity of the issue. Where did all these rude, angry, old people come from? If this is how we have a conversation, I fear for the next generation. I have been sickened by what I see as the triumph of ignorance and resulting pandering by the politicians who over-estimate the power of these individuals, if not the corporate money behind the strategy to terrify and misinform them.

An additional problem is that medicine is an art. In a practice based on science, the practitioners are humans who cannot possibly be expected to serve their patients flawlessly. Misjudgments happen and that is the way it is.

It annoys me that the question of better “outcomes” is always defined by the cost associated with it and whether that cost is “worth” it. My near-death experience in 2000 was an eye opener for me. My doctor told me I had the “gold card of insurance” and therefore I had a good chance of survival. What about all those others who do not have this care? I assume they may not survive.

With universal access to health care—and a huge educational effort in our schools and workplaces to recognize health care as a priority for a healthy and fair society—many of these problems are automatically solved. However, until we stop discriminating against people with poor genetics or who are unfortunate enough to be sicker or older than the norm, it will be unfair and un-American in the truest sense.

What we tend to forget is that illness, untimely death and disability ruin lives and families. If one examines genealogical trees for proof or even statistical significance in this regard, those with the best health are able to accumulate more wealth, gain greater power, bear more children and have a greater quality of life.

Other than fat people—who are discriminated against in society more than any other group—sick and disabled people are the next most discriminated group. Sadly, poverty also contributes to obesity in this country, as high-load refined carbohydrate foods are incredibly cheap.

I still wonder how so many mean-spirited people, narcissistic beyond belief, end up being given such high profile in the news media, and then I remember the media is controlled by those business interests seeking profit and power.

Candidly, I need to meditate more myself and cultivate gratitude, but this is hard to do when I see children laughing at the park and notice their mouths are filled with cavities or I learn of a family whose baby died because the parents hoped he or she would recover without seeing a doctor.

Allowing these vulnerable innocents to suffer is unconscionable and immoral. I’m sorry if some people in our society will have to take a pay cut or make less for a necessary service, but allowing anyone to take advantage financially for the necessities of life? This is not freedom for any of us.

I sincerely hope our new president doesn’t cave in to those who stand in the way of progress. Our medical care system has many options. In France the people are the happiest with their health care, but so are those in Switzerland, Germany, England, Canada and the rest of the developed countries where health care is universal.

Why we Americans insist on being so backward—evidenced by our death penalty and health care delivery policies—is beyond me. The people I know seem so intelligent and good. Who are these other people? Their mothers would be ashamed of them, that much I can guarantee.

If I might add to my previous comments:

You are absolutely correct that medical records upgrades are a critical factor in both improving outcomes and decreasing cost; I leave that to the for-profit consulting sector that I hail from (Deloitte & Touche, IBM).

My goal is to address the health care claim as a completely separate issue because the lack of uniformity is pervasive, it is a huge time and money waste, it can be fixed by freeware programmers working from home, and only federal government can provide the discipline of making the use of it mandatory. In other words, it is the proverbial “low hanging fruit” that would by itself free up 20% of doctors’ time and impact costs throughout the entire industry at the same time. I want to be the “Susan B. Anthony” of that particular issue.

As for addressing the health care/health insurance issue by Thanksgiving, I must interject a little history here. Various bills and comprehensive programs to create universal or widely-extended health care or health insurance have been floating around Capitol Hill for many, many decades. As far back as Teddy Roosevelt, full-scale health care has been attempted many times. My own grandfather, a horse-drawn ambulance driver for Bellevue Hospital (his red dray is on display in the lobby at NYU) served on a commission with Eleanor Roosevelt in the early 1930s to add health care for all Americans to the Social Security Act. No go. Following that, another complete program was presented by Harry Truman. It got some play with Johnson as he considered Medicare.

All the electronic transactions were defined by Jim Moynihan and Marcia McLure in the early 1990s, but the Clinton reform died on the vine. The hope of health care reform has been kept alive by Ted Kennedy since. Even my own Congressman, Stark, came up with a comprehensive bill just last year.

There’s more history and our legislators are more versed on the pieces and parts of this issue than any other. Given that there’s a high-cost chokehold on those already insured and that 17,000 people per day lose their access to health care and join the 47,000 already uninsured, I think it’s time.

As for the future, my daughter is a May, 2009 NYU med grad and intern at Bellevue in emergency medicine. I’d like to give her the gift of getting this solved on my watch.

I’d like to offer a couple more thoughts on this very well written piece:

1) Have you ever heard any doctor not complain about malpractice insurance? It’s outrageous yet necessary because people feel entitled to sue their doctor when something goes wrong (or seems to go wrong). We really need some sort of tort reform, but that’s unlikely because of the campaign money going to the democrats.

2) I agree with the comment about hypochondriacs. One of my best friends goes to see a doctor at least once a week. Of course his insurance covers it in full. If he had to plop down $100 each time his behavior would change.

3) This “health” bill contains too many riders to satisfy the friends of the ruling party. Why does this bill contain a provision for taxpayers to pay for the “pension” of the ACORN group and others? Granted, this is the way we do government, but for something this important, can’t we just focus the money on health care?

4) The debate about end-of-life is taking away from the real issue—how will we ever pay for this? Shifting the payment to the government isn’t a solution. Look at all the pension obligations we are already on the hook for. This country is going broke fast. I’d love the debate to target how much this will cost and how we will pay for it.

Excellent piece of writing, Alex!

[…] […]

I went to the emergency room for a panic attack once (I’ve only been twice in my life, don’t accuse me of overutilizing!), and the treatment they gave me was half a pill of lorazepam.

When I got the bill later, which was itemized and showed how much everything had cost me, I looked it over and saw that they’d charged 50 dollars for that half of a pill. Now if we check how much one 2 mg pill of lorazepam costs, it’s about 75 cents. That’s over a 600% markup!

Whenever I hear about skyrocketing health care costs I remember that bill. Maybe next time I’m in the hospital, I’ll ask what medication they want to give me, and have a friend go down to the drugstore and pick it up for me. It’s certainly a lot cheaper.

[…] A Prescription For The Health Care Crisis Albert Einstein is reputed to have said that if he had an hour to save the world he’d spend 55 minutes defining the problem and only 5 minutes solving it. Our health care system is far more complex than most who are offering solutions admit or recognize, and unless we focus most of our efforts on defining its problems and thoroughly understanding their causes, any changes we make are just likely to make them worse as they are better. […]

Our health care system is based on the Puritanical ethic that if you work, you are human and therefore deserve health care.

Never mind that for 100 years we were shipping slaves out of St. Augustine.

Until we tackle economic inequities—gender, class, race, citizenship—we will be tilting at windmills.

It’s really all about value judgments. The Europeans pay very high taxes for their health care, while in the U.S. we prefer to pay for defense. How long did it take to authorize going to war in Afghanistan and Iraq, and that cost could easily have paid for years of health care for everyone in the U.S.

Americans began as a very independent people: do-it-yourself, pull yourselves up by your bootstraps like I did; ignoring the fact of birth, good parents, education, and more gave them a head start over the less fortunate. If we truly cared for others—which is the theme for initiating democracies in foreign countries—we would first and foremost care for our own citizens. It can be done. Do we have the will to do it?

Missing from this analysis is any mention of a single payer system. It’s used in Germany, France, the Netherlands, Great Britain, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Ireland, Belgium, Italy, Japan, Canada, Austrailia, New Zealand—all countries with equal amounts of conservatives and liberals. The citizens of these countries enjoy better health by almost every measure—life expectancy, child mortality, debilitating illness, mobility. Gee, could they be on to something?

Instead of examining that elephant in the room, you propose five “feel good” solutions that require the various players—the insurance companies, the patients and the health professionals—to be nicer and not so self interested. Yet you expect these solutions to work by preserving the free market. I’m all for the free market when I buy steak, toilet paper and a computer, but when are we going to learn that some services and products—education, utilities and health care—are more effectively distributed by public means? Oh, and please no snipes at public education unless you are prepared to compare literacy rates in the U.S. with those countries that have no public education at all.

I pondered your post last night and decided that health care costs can not be controlled. A majority of the stake holders are for-profit and answer to a higher power such as stock holders, venture capitalists, management, family, etc. Each year they set a budget and focus on making the numbers, anyway they can.

We know that drug companies post next year’s price increases in the Fall, simply to clear out inventory by the end of the year. Every stock issuing company is under profit and growth pressure and the largest insurance companies have multiple opportunities for losing money, much like AIG operating like a hedge fund. From our perspective we can dissect out cost saving processes but we miss the big picture, which is pressure to grow and increase profitability. Health care is not really scalable so income growth is achieved in other ways, increasing market share, recovering more dollars per patient or selective denial of service.

This is not a rant against capitalism but an observation that no stock analyst will accept a company that says they are reducing profitability, even when the whole economy is tanking. People jettison the stock. Government payer programs are captive to the profitability demands, not paying more for a procedure but paying for more procedures, seeming over utilization. Certainly a well equipped specialty clinic with an under utilized imaging device looks at it as a profit or loss center. Health care is a business subject to all the business rules.

Issues with cost containment begin when you define how health care businesses should be run without running the business, yet these are businesses that charge vastly different prices for the same procedure. The only explanation being that the components are treated as cost centers and the sum of the components produce price distortions. There is no integration discount. An $800 MRI costs $5000 somewhere else. The $65 pill includes the pharmacist’s time and the delivery time to the bedside plus follow up. The bill was coded by a person with a high school education. The word complex adds $10,000 to every process.

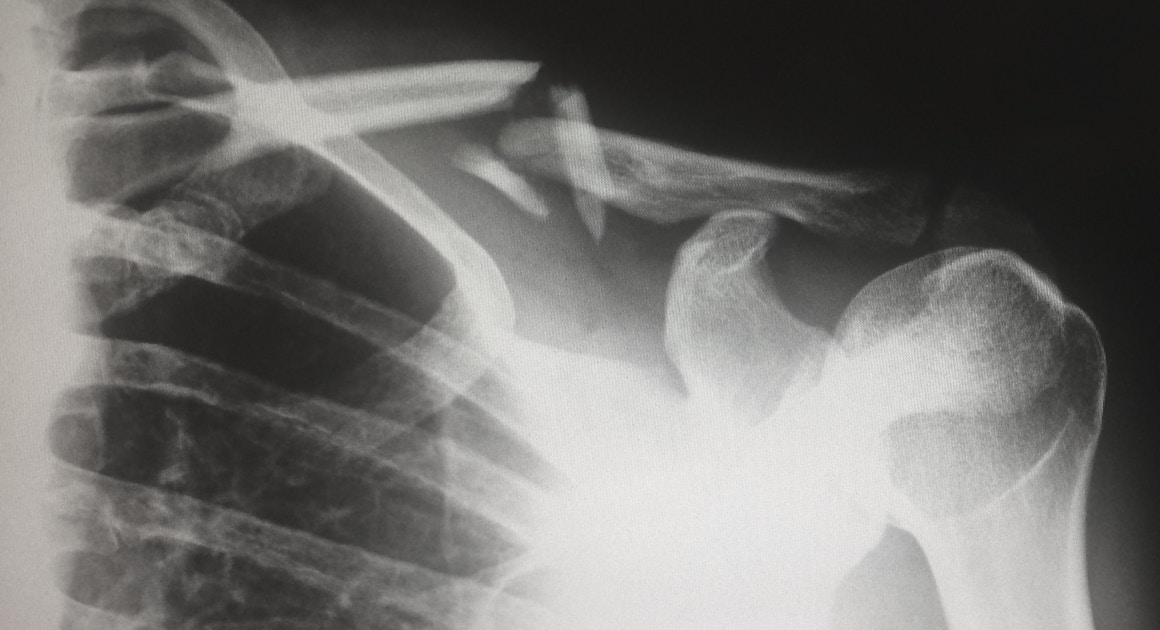

Cost control measures have been suggested such as high barriers to care at the local level to prevent over utilization. My neighbor has a broken collarbone that was diagnosed but not treated. The bill was $1100, almost what he earns in 3 months mowing lawns. Many poor people are wary of hospitals as often their relatives walked in and left feet first. Care is delayed rather than over utilized.

I understand that rural sponsored health clinics and fairs are very cost effective at delivering care. Perhaps medical school tuition can be linked to public service. The most creative solutions tend not to be for-profit.

In reading through your blog and the comments, I ran across the anecdote from Josh about the charge for a half tablet of lorazepam. Everyone can get outraged about that kind of “overbilling.”

However, hospitals are obligated to provide lots of care to people who don’t pay, can’t pay or won’t pay. So we, who have insurance, pay for them. Like it or not, the cost of my insurance premium is high because when I go to the hospital for an emergency and my insurance company gets charged for things like $12 aspirins. I’m just helping to cover the poor woman in the emergency room who has no health insurance and has a baby with whooping cough or something like that. And, in this economic climate, more and more poor people without insurance are having their costs covered by us.

That’s why we need reform. Everyone has to be insured somehow. Otherwise we all just continue to see our premiums jacked up to numbers that are out of sight.

By the way, on overuse: I read in the Times last week that there are 62 million CAT scans done in this country every year. There are only 300 million of us. That’s the craziest number I’d ever heard…

This is one of the best discussions that I have seen, particularly in that it has not degenerated into partisan rancor. So, to all who have participated, good show!

I just have a couple of things that I would like to add. Regarding tort reform—I agree that tort reform is appropriate. I have wondered why doctors don’t risk pool their malpractice insurance in the same way that lawyers risk pool their malpractice coverage. Obviously, the amounts paid would need to be commensurately greater, but PLF (professional liability fund) coverage for attorneys in my home state, Oregon, runs around $2500 a year. The pool is administered by the bar association and is run as a non-profit.

I’m not a plaintiff’s attorney, so I don’t have a vested interest in the litigation lottery, but it’s also my understanding that states that have implemented tort reform have seen neither a drop in health care expenditures nor a drop in malpractice insurance rates. Rather, I think that the insurance companies insuring for medical malpractice just make more money. People who are injured through medical negligence should be made whole to the extent possible, but gargantuan awards, like punitive damages, should be reserved for cases where the doctor engages in bad faith or gross negligence.

I believe that the most important step that we could take would be to de-couple health insurance and employment. Legislatively mandate that health insurance cannot be purchased by or through employers, and with that mandate require that employers pass the money that they have previously used to buy health insurance to their employees in the form of pay increases.

Add a public insurance option with three levels of available coverage (major medical/catastrophic, standard, and total) and require them to offer coverage to everyone at the same cost. Private companies can compete, but they must agree to no more exclusion for pre-existing conditions so long as the individual consistently maintains health insurance with someone. If an individual allows their insurance to lapse, they can only reinstate coverage by back-paying the premium for the period that they have lapsed. Anyone making under a certain amount of money is automatically enrolled in the basic public option.

Require hospitals/doctors to post prices for procedures and consultations, and end the bizarre pricing discrepancies that have private pay patients being billed for double or sometimes even 10x the amount that the insurance companies reimburse for their patients. This would help the market to exert some downward pressure on the cost of health care. It’s impossible to cost-comparison shop for medical care, because there is no way to determine how much something is going to cost. The doctor doesn’t know what his rate is until he knows who insures the patient (i.e., how much the insurance company will pay). This is crazy.

Finally, expand funding for palliative care specialists and other end-of-life care. Americans are terrified of death—it’s as though we believe that we can defeat death itself so long as we throw enough money at it. Nonetheless, one thing is certain—we are all going to die someday. Many people would choose a simpler end (I believe) if they truly knew what their options are, what the risks of the heroic treatment are, and how much it would cost.

I’m not suggesting that we should have accountants making decisions about denying potentially life-saving treatment. I’m talking about the people who are terminally ill, and the question of what we should be doing to prolong their lives.

This was a great read Dr. L! Even an ignaramous like me could understand this. You have a new fan.

[…] […]

I have to strongly dispute the “tort reform” aspect—as the recipient of some truly awful medical care, I definitely agree that some kind of change needs to come to how patients and doctors are compensated for medical error, but it can’t come exclusively at the expense of patients.

Doctors have shown themselves too interested in protecting the reputations of bad doctors at the expense of physicians as a whole. As a consumer of health care, it is nearly impossible for me to gain access to any sort of a fee schedule or doctor’s history. Any market based system can only work in the context of knowledgeable consumers. Moves away from informing consumers about doctors and their success rates are moves away from the market.

With reference to your request for data demonstrating that citizens of countries with single payer systems “enjoy better health”, e.g., life expectancy and infant mortality, than the US: https://www.infoplease.com/ipa/A0004393.html.

A number of the European countries that rank better than the US in this table have single payer approaches. The relationship between single payer and superior expectancy/mortality statistics is only correlative, not causative; however perhaps it is equally relevant to point out that these single payer countries expend less on health care per capita and as a percentage of GDP than does the US.

“Change the way insurance companies think about doing business.”

This is like asking cats not to go after birds. A better option would be to cut out the middleman. Looking at the big picture, insurance companies bring very little to the table…and they know it.

I found this blog from your post on the NYTimes article, “The Fight of Her Brother’s Life.” This is an excellent discussion of a very complex topic and I recommended it in my own post on that Times piece.

Love the rational non-partisan tone of this blog as well as the comments. I might also suggest that readers try to see the documentary (on PBS) or read “Money Driven Medicine” by Magie Mahar who discusses both the high cost of technology and over utilization as major contributors to the problem, lack of PCPs and that health care is quantified by cost not by outcome.

I myself am caught in the gap between unemployment and Medicare, so I have a strong interest in the health care debate.

Answers are easy, it’s the questions that are hard. Articles like this contribute to our understanding of the underlying question of how things got so out of hand. There are actually a multitude of solutions that exist right now that any one or a combination of could effectively deliver an improved result.

But underlying the whole debate has to be the belief that the needs of society are more important than the rights of shareholders and consumers are first and foremost citizens who have a fundamental right to health care. This cannot just be a political soundbite.

Thanks again for referencing your link in your Times post. I’ll be an avid reader!

Thank you for the refreshing, thoughtful rationale without political rancor. This week a group with similar spirit from the Brookings Institute published their recommendations for reducing the long term growth of health care costs. The 10 page article is “Bending the Curve” and can be read at:

https://www.brookings.edu/reports/2009/0901_btc.aspx

Since the White House has called on Congress, the insurance industry, and the nation to “bend the curve,” my thought is that this report might be used by the administration. Myself and many of your readers would be interested in your opinion of the report.

For the truth about our present healthcare costs, read Darshak Sanghavi’s excellent explanation on Slate, of Sept. 2. He is a pediatrician at John Hopkins.

In 1985, an economist (!) developed the “relative value scale” by which physicians are still paid. It is used by Medicare and the AMA and all major insurers use it. It places far more relative value on fancy procedures like stents, EKGs,CT scans, skin biopsies, and bowel clean-outs than on face-to-face encounters absolutely necessary for referral to the specialist. That is why there is now such a drastic shortage of family practice physicians: they are the lowest paid of all physicians, and in a recent class of residents at Massachusetts General Hospital only one out of a class of 50 planned to become a primary care physician.

There is no reason we can’t have a government system competing with private, if the private sector is so good and efficient it should certinly compete with, if not crush a bloated, uncaring bureaucracy. The same mentality that stands against government health care is the same mentality that has outsourced our prisons, military and intelligence service. We all but outsourced a war; how well did that turn out?

[…] Prescription For The Health Care Crisis By Mike good article on healthcare reform in the States that in my view also applies to many other healthcare systems […]

THANK you all for your intelligent, insightful thoughts on improving our health care system. I know that our health care system is badly broken. I am wanting and willing quality health care for all Americans. I pray that we have the wisdom and will to make it happen.

Peeking at you from north of the border. Just like to make a few points.

1—US dollars per capita is very misleading because all other countries you compare yourself to have coverage for 100% of population. 50+% of Americans declaring bankruptcy due to health expenses have coverage of some sort. I have never seen statistics showing % of Americans with partial coverage or caps to coverage.

2—It isn’t just the profit of the private insurers that is an expense above that of a public system. Public insurance systems don’t employ people to reject claims or people to check when coverage limits have been reached or people to reject applicants. Canadian doctors don’t have to sort out which insurer to bill or to receive permission from or worry about whether this is a collectable account.

3—Because of single payer, fraud is less.

4—Technical innovation is a double-edged sword. I read that there is resistance in the US to new recommendations on mammogram testing for women under 50. These recommendations have been the Canadian standard for years. Not because we can’t afford US standards but because in women under 50 without a family history of breast cancer the false positives outweigh the benefits. MRIs are wonderful machines but the average human body is riddled with blebs and blobs that require further and more invasive and expensive examination.

5—Canadian system is not really single payer. The federal government gives each province a per capita sum based on population which is inadequate to provide health care to a federal standard. The shortfall is made up from provincial resources. Thus we have 12 health providers from which to derive a “best practices” check. And, of course, 12 different standards of health care though certainly less than that between Wisconsin and Louisiana.

6—I am happy with the health care I get for my $624 annual fee. Are you?

Alex, M.D.,

I am months late in responding to this. I’ve just discovered your site. Apologies for being late; I can’t wait to see the rest of the site.

By way of background, I recently (July ’09) got on the patient list of a wonderful PCP who works for a medical school. It took > three months to do so and my PCP would never have accepted me as a patient were it not for her friendship with someone we mutually know. She is overloaded with patients, utterly overwhelmed. She sends me emails at 10 PM to volunteer to get me lab test scripts, but she cannot see me unless I somehow figure out how to break a bone with at least two month’s advance notice.

All my doctors now work at the same medical school. If I understand this correctly, that means they get paid a salary and don’t get paid for ordering extra tests. I’ve never had so many damn tests in my life! Is it possible that because they don’t have to worry about what insurance companies will reimburse them that they actually order more tests than a doctor in private practice? Just asking.

I am appalled at the medical care I get—I guess I grew up in an era where your local doctor was the go-to-guy or gal if you broke a wrist or a rib. I can’t do that today. The ER has become my de facto PCP. I have insurance. $710/mo insurance and it is not widely accepted because my plan reimburses at Medicaid rates. It comes with a high deductible and high out-of-pocket limit. It also comes with the nightmare condition that BCBS can cancel my insurance immediately if I am ever late on a single premium payment. They’ve done it once when a December 2004 check was “never received.” I was perfectly healthy at the time, so the caller told me I could be re-enrolled, but my premium would be hiked 20%. After the medical problems I have had this year (minor, but they lost money on me) I know I won’t be offered that option again should another payment miss by a day.

I’ve learned the hard way never to go to the ER by asking a friend to drive you. It’s farcical, but calling 911 and arriving in an ambulance means you will be seen in minutes and not ten hours, as happened the last time I made that mistake.

This system is not working. It can’t possibly be a good use of ER doctors and staff to mend slightly-fractured bones. It can’t be a good use of our (hey, tax-payer-funded) ambulance services to drive people who are not seriously ill to ERs.

Next, the paperwork and the faxing. Both have to stop. Every time I see any doctor at this school, I need to allocate 30 minutes to the paperwork. They are so afraid of a lawsuit, they print out 40 labels every visit and then affix them to multiple duplicate copies of forms that will help them avoid lawsuits. They routinely ask each other (in late 2009) to fax reports. Is the medical community unaware of the power of, say, the PDF file format and the existence of email?

Finally, we need more PCPs and walk-in-clinics staffed by P.A.s or RPNs. We need so many more of these. I don’t think the folks who are writing this bill have any clue about that. They of course have the best health insurance in the world and probably schedule appointments with their PCPs when they sneeze.

Christine, thank you, you offered excellent ideas which really resonate with me.

I feel so lucky because my internist acts as if he has plenty of time to talk with me. i think the reason for this is that he is a high-level, highly-paid hospital executive and practices part-time.

Re: pricing of tests:

They are totally opaque to doctors as well as patients. They depend on which insurance you have, or don’t have. How is that reasonable?!

I think the issue of saving the private health insurance industry with the amount of taxpayer subsidies needed to insure everyone boils down to a moral one. For over thirty years, the private health insurance industry has denied coverage to those whose only sin was to actually get sick before they needed coverage. During this period of time, they have selectively chosen to insure those least likely to actually need health care, while neglecting the rest. They have stood idly by as millions of people were forced into bankruptcy because they got sick and the insurance company denied paying the claims, or refused to provide insurance in the first place. And during these three decades, this industry has shown absolutely no interest in voluntarily changing so that all Americans can receive access to affordable health care. No, what they have done is “dump” on the taxpayers all of the citizens they cannot make money off of.

This is a moral issue and that is why there is not another industrialized country in the World that has given private health insurers such latitude in running its health care system. Citizens in other countries can see a doctor (not just the ER) even if they don’t have money, or have a pre-existing condition. Even those countries that provide a place at the table for private insurers only do so with regulations no insurance company in America will every tolerate. Regulations that no Congress will ever impose in the face of lobbyists throwing money at their campaigns.

We can debate the merits of reforming the private system while tens of millions of our citizens die because they have no insurance, or go bankrupt because they cannot pay the bills. It says something about the moral makeup of a country that is the richest in the world, yet cannot provide basic care to all citizens.

I understand these are complex questions, but please, other countries have systems that provide care to everyone. We can argue about whether their systems are as good as ours, but if you cannot gain access to health care (not just the ER), it really does not matter the degree of difference. Private health insurance is unsustainable, and if you have children, it should scare you to death that they will be forced into such an inhumane system.

Thank you for a well-reasoned post. I have three concerns I would like to raise for your consideration.

First, I notice that your FIRST premise for this conversation was “cost control.” How can we have costs before we have a program? In my view the first step has to be describing the kind of health care system America wants. Is it one where wealthy people obtain the world’s best coverage, while millions go unserved? Is it one where fundamental medical decisions are made by neither doctors nor patients but self-interested third parties? Is it one where 1/3 of all health expenditures go to managers and shareholders? I assume the answers are no, of course.

This is not mere sophistry: If we approach health outcomes from a primarily (or exclusively!) economic perspective we will inevitably find ourselves putting dollars and cents on people’s lives and welfare. A system that begins with healthy outcomes does not put a price on everything; it prioritizes outcomes but on a health, not economic, basis.

Or, from a slightly different perspective, I would say that a public system will see expanding overhead eating away at health budgets when administrators are doing a poor job; for-profit providers and insurers will see their own expanding overhead eating health budgets when they are successful at enhancing their revenue and profits. In one case, diversion of health money to administrators is a mistake (transparent and correctable by taxpayers), and in the other it is the purpose (hidden and encouraged by managers and shareholders). This is why a public option is necessary and a public system will inevitably outperform the present system in BOTH outcomes and costs.

Second, you quote your colleague: “as Bala Ambati mentions on his blog, Daylight’s Mark, the U.S. has larger minority populations than many European countries riddled with issues well known to compromise health outcomes (poverty, increased crime, higher risk of death by homicide to name a few).”

This is commonly repeated but essentially false information. There is no support whatsoever for the alleged connection between the US minority groups and health outcomes. First, Canada, France, and Germany all have public health systems with superior outcomes and similar proportions of immigrants (Canada has substantially more than the US). Second, it is obviously the social inequality and poverty of these groups that is the problem, not their ethnicity: there is a correlation, but the causation Ambati and others conclude is entirely false.

The presence of minorities is an *excuse*, not a reason. It’s factually incorrect and racist and should not be repeated by reasonable people, in my view. Ditto goes for America’s murder rate—while Americans do kill each other with remarkable regularity (3x as frequently per capita as we Canadians, for example) that shocking figure is still insignificantly small compared to the overall number of deaths and does NOT warp the national statistics. Americans die younger than Canadians not because of guns, but because they eat too many big macs and maybe 10% have no health coverage at all. Show me any country where 10% of citizens have no health care, and I will show you a country with worse outcomes than Canada, no matter how many people carry guns (and PS per capita gun ownership is higher in Canada than the US, little known fact).

The evidence is clear that most wealthy western nations obtain as good or better outcomes with a smaller investment as a proportion of GDP. Americans pay more and get less, and that is the problem the US needs to solve; making spurious (and racist) excuses for the data is not going to be helpful. Americans deserve the best care, and they don’t get it, and one of the main things stopping them is their firm but mistaken belief that their system is “the best in the world.” It’s not. It *includes* the best health care in the world, but that’s not the health care that most in the system get. Overall, Americans are being ripped off, period. They should be mad as hell about the coverage they are getting, and instead they are fighting to keep it!?